- Home

- Zoraida Cordova

The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina Page 12

The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina Read online

Page 12

Tía Pena glided like the wild breeze she was, like she was still underwater. She traced her daughter’s face and tried to talk. But when she opened her mouth no sound came out. Pena drifted across the room to her mother, holding her delicate throat.

“Pena, mi Pena.” Orquídea wept glittering tears. Caleb Sr. and Héctor and Martin followed suit, kissing her cheeks, her forehead, then joining the others around her, waiting like reapers.

Orquídea extended her arms, which were sprouting branches of their own. Green nubs edged their way out as they started to become leaves. “Marimar, sit here, bring me Pedrito.”

Marimar took the seat left open for her beside Rey. She handed over the baby like he was made of tender flesh and blood. “What happened to him?”

Orquídea held the moonstone baby in her arms, right against her heart, like she could make him a part of her if she tried hard enough. “He was my first son. There was a terrible accident that also took my first husband back in Ecuador. I couldn’t save Pedrito. It was all my fault.”

“Why didn’t you ever say anything?” Félix asked.

“There is so much I can’t say. I can’t. Long ago, I made a bargain. Everything I have, everything I’ve ever given to you came at a cost. Even this house.” Orquídea, surrounded by the living and the dead, smiled as the clock rang the ninth hour. “Please, let’s eat. I’m running out of time.”

“That’s it?” Enrique asked harshly. “That’s all you’re going to say?”

“Why are you doing this?” Marimar asked. “What can’t you say?”

“For you. For all of you. We become what we need to in order to survive and I need to make sure that you are all protected.”

A knot formed in Rey’s throat.

“It’s not what you all want to hear, or what I want to say. But it is what I can manage.” Orquídea shut her eyes. Her thumb, which was now twisted at the tip like two vines intertwining, brushed the back of Pedrito’s head.

“You never give a straight answer,” Enrique said.

“You never ask the right questions.”

Enrique stormed out of the room, stopping for a moment in front of his father. It was like looking into a mirror that revealed your future self. But not even Caleb Soledad could staunch Enrique’s rage, and he barreled through his father’s ghost.

“He’ll get over it,” Félix said.

“He won’t, but you heard what Ma said. Eat.” Tía Silvia, whose tears ran down her face in glittering rivers, piled food on plates. Goblets brimmed with the deepest red wine. The spirits ate and ate. The living hurried to tell their stories, their accomplishments, their wins, their progeny. Martin vanished for a moment, then returned and the sounds of Orquídea’s favorite songs filled the house, which had been empty and silent for too long.

Gabo’s cry cut through the music, the chatter of voices from the living and dead. Orquídea looked out the window at the moon, perfectly aligned to her needs. She was running out of time. She had wasted so much time.

Marimar turned to her grandmother. “You can’t leave yet.”

“Oh, Marimar. You’re a bright, wonderful being. Do you know what I love about you?”

Marimar shook her head.

“I love that you care about people. You know how to love. I taught myself not to. Someone in my bloodline had to make up for everything I lacked.”

“How could you not know how to love?” Penny asked. “You were married five times.”

Penny’s words, innocent if rude, made everyone laugh. Orquídea sipped her bourbon, and it burned the whole way down. Her movements were getting slower. Her bones ached as they transformed into someone different. Something else. But she held on tight to her firstborn son and said what she had to say.

“Love and companionship are different things, Penny. I have made mistakes out of fear. But this?” Her eyes roamed the room to look at each and every member of her family. “This was not one of them.”

“What mistakes did you make?” Gastón asked.

“The bargain,” she said. “Forty-eight years ago, I made a bargain and it cost so much more than my silence. This is the only way I can protect you from him.”

“From who?” Rey asked.

A hard wind snuffed out the lights on the windowsills as dozens of dragonflies and fireflies flew in. They were followed by hummingbirds, blue jays, and larks. Frogs and newts. Snakes and lizards. Field mice and rabbits. They came all at once, filling the room. Some crawled into empty bowls, others perched on chandeliers and wine goblets. Penny gathered a rabbit to pet between its ears. The twins sprung out of their seats trying to catch snakes.

Florecida, who had a fear of mice, hopped up on her seat. Tati tried to calm her down, but Mike Sullivan had gone faint and fallen over his chair. Silvia sprang into action, checking his pulse and shining a light in his eyes. Penny gathered the mice out of the room. Meanwhile, Gabo crowed again, and the spirit of Luis Galarza Pincay danced with his daughters to the plucking sounds of guitars and boleros. Marimar wondered if they were truly ghosts, or if they were impressions created by Orquídea’s sadness. After all, if the dead could rise, then why hadn’t her mother come to her sooner?

Juan Luis and Gastón began to choke. They raised their hands in the air and Rey hit their backs until they coughed up identical balls of hard phlegm.

“Cool,” they said in unison and picked up the slimy things, as Rey muttered, “Disgusting.”

Enrique thundered down the stairs and rushed into the living room. A sparrow flew at him, but he swatted it away with the papers in his fist. He held a finger to Marimar like a cocked gun. “You’re leaving the house to her? She’s a child!”

“Marimar is nineteen. Aren’t you?”

“I am.”

“This house belongs to me,” Enrique said. “Why do you think we all came here? Because you were such a warm and loving mother? You show that stone thing you’re holding more affection than you ever did any of us. I’m not leaving without what’s mine. This land is rightfully mine.”

“Nothing is yours, Enrique,” Orquídea shouted. “You don’t have the first clue of what I did to survive. To make something out of absolutely nothing. I did what you don’t have the guts to do. You want to fight over a bit of dirt? It’s too late. It’s done.”

The animals in the room buzzed and croaked and hissed louder. Tatinelly made a sharp gasping sound and the house shuddered, cutting off the electricity so that the only light came from the fireplace, the dripping candles along the center of the table, and the moon shining through the window.

“Why make us come here?” Enrique asked, breathless as he slumped into an empty chair. His father’s ghost appeared beside him and rested a hand on his shoulder. “Why aren’t the rest of you angry with her?”

“We are, I think. But we can’t change her,” Caleb Jr. said.

Everyone nodded. Félix yanked off the crunchy ear of the pig and Ernesta joined Rey in opening a new bottle of bourbon.

“To the Montoyas,” they said, and clinked each other’s glasses.

“If you look closer at the invitations, there is something for each of you,” Orquídea said and gestured to the twins.

Gastón had picked up the phlegm they’d coughed up. On closer inspection, it wasn’t phlegm at all. They were seeds.

Around them, more Montoyas doubled over and coughed and coughed until they spit up seeds of their own, glossy with saliva.

“It’s done,” Orquídea repeated. The next breath she took looked pained. “When I’m gone, you will have each other. Plant them. Take care of them. These seeds are your protection against the one person I cannot fight.”

“Who?” Rey asked.

When she tried to speak, his grandmother coughed up mud. Shaking, she turned to the dead, and said, “Take me.”

The ghosts walked through her, and then, one by one, they were gone.

“Perhaps now I’ll finally have peace” Enrique said, angry tears streaming from his hungry eyes. He

wiped at the corners of his mouth, got up, and threw his seed in the fire.

Orquídea stood as much as her legs would allow. Everyone, except for Enrique, moved to help her. They gathered around, but she wanted to do this on her own. At first, she wavered, her body attempting to balance on the roots that devoured her legs. When she was steady, she poured the last of her bourbon. She hummed the last line of the song. She turned to her family and raised her glass with one hand and clutched Pedrito with the other.

“All you have is each other. Protect your magic.” She drank and then shattered the glass on the floor.

For a moment, there was only the buzz of thousands of wings, the crackle of fire, then the howl of every creature in the room. Beneath all of that, a series of heartbeats. Each one with its own unique rhythm of wishes and hopes and dreams. The symphony of Orquídea’s death.

Tatinelly slammed her palm on the table, the other on her baby bump and the earth rumbled. Orquídea Divina Montoya stretched higher and higher. Her legs finished transforming into the base of a thick tree trunk, roots undulating through the floorboards like rivers carving their way through stone, pushing away the table, breaking through the nearest wall, the ceiling.

“My water broke,” Tatinelly announced with a gentle gasp. She lifted her shirt, revealing the pearly stretchmarks across her belly. A rose grew out of her belly button. “My water broke!”

“Upstairs! Juan Luis, get the bag out of my car.” Tía Silvia shooed everyone out of her way. “Someone, for God’s sake, wake up that man from the floor and tell him he’s about to miss the birth of his child. If you can’t make yourself useful, stay here and clean up. That guest room better be spotless.”

“It is,” Tatinelly assured her, as they left the room. “It’s like she knew. She knew.”

After Rey called for help, he and Marimar pulled up a seat at the destroyed banquet.

“Did you cough up any magic beans?” Rey asked.

“Nope. I just get this house, apparently,” Marimar said. Most of the glasses were shattered, so she drank straight from the bourbon bottle and grimaced.

Upstairs Tatinelly’s screams were piercing, competing for attention with Gabo. She could hear Tati’s frantic pulse in her ears, plus a second heartbeat—the baby’s. Marimar’s own blood was like fire beneath her skin. Something hot and piercing stabbed at the notch between her clavicles. But she ignored it as Enrique stood before her.

“You always were her favorites,” Enrique said, his eyes pale, ensorcelled by his own hate. “Sign over the deed, Marimar. You don’t know the first thing about fixing this house. It’ll be worthless once she’s done.”

The house groaned around them. The tree still growing. At its center was a smooth heart made of moonstone.

“You’re wasting your time,” Marimar said. “I’m not signing over anything to you.”

Rey got between them and shoved Enrique. “Leave. You didn’t want to be here in the first place.”

Enrique threw the first punch and Rey was slow with drink, but he punched back. Marimar shouted around them to stop. Orquídea was dead and Tatinelly was giving birth upstairs. There was no time for this. She picked up an empty bottle and hit her uncle across the head. He fell to his knees, nursing the spot. His eyes regained their jade color. He watched in horror at the sight of his mother’s tree, then turned to the open windows.

A storm of dragonflies clustered around him, their tiny arms and legs crawling all over his face, his eyes. A frog leapt into his mouth when he screamed, and a snake wrapped around his throat. He tried to pick himself up but yanked on the tablecloth, knocking over candelabras.

The fire caught fast. It spread along the tablecloths. The stuffing inside Orquídea’s favorite upholstered chair. The alcohol-drenched rug and the floorboards.

Upstairs a newborn’s cry pierced the night.

* * *

Tatinelly got her wish. She didn’t know why but, despite the pain of the delivery, she was overcome with a certainty that her daughter would be okay. Even though she’d grown up to do ordinary things, she would have an extraordinary daughter. She promised to tell her stories of her Mamá Orquídea who built her own house in a magic valley. Mamá Orquídea, who was strong and angry and silent, but saved her real love for when it mattered.

Earlier that day, Orquídea had called her in.

“Tatinelly,” Orquídea had said. “Let’s see you. Come.”

Tatinelly waddled around the table and took the upholstered seat Enrique had vacated. “How are you, Gran?”

“My bones are weary. But I’m happy you came. It’s been so long since we’ve had a baby in the house. The last ones born here were Juan Luis and Gastón.”

When Tatinelly sat, her shirt rose up a bit. Her belly button looked like the bud of a rose.

Orquídea held her hand out. “¿Puedo?”

“Of course,” she said.

Orquídea placed her free hand on the top of the belly and closed her eyes, as if her fragile bones could protect that child from the world. She listened. What was she listening for? Could she hear the stars in her womb? Were they whispering now? Just then, Orquídea Divina’s hand grew a single white rosebud in the fleshy web where her index finger met her thumb. The old woman took a deep breath and a deeper drink of bourbon.

“A girl. Good. Be good to her,” Orquídea Divina said. “Let her run free.”

“Thank you, Gran,” Tatinelly said. “I’m sorry I didn’t get to visit more. I always meant to and then things just got in the way.”

But the old woman dispelled the apology with a wave of her hand and the blooming rose that had grown so quickly, withered into dust seconds later.

Then, Tatinelly felt a kick, a sharp pain. The sensation gathered at her belly button, where a quarter-sized flower bud had sprouted. She looked into Orquídea’s eyes, sparkling and black and wet, and didn’t have enough words for what her grandmother had just given her. A gift for her daughter. Something extraordinary.

“Do you have a name yet?”

“I do. It’s—”

“Don’t tell me! I want to be surprised, too.”

* * *

As Rhiannon Rose Sullivan Montoya came into this world, twenty-eight days early, and was placed in her arms, Tatinelly was sure of two things.

The first was that her daughter was special. All kids are special to their parents, she supposed. Tatinelly hadn’t been special. She’d been ordinary like her mom and dad. But not Rhiannon. The quarter-sized bud that had sprung from Tatinelly’s belly button now blossomed at the center of Rhiannon’s forehead. It was the most beautiful thing she’d ever seen. A tiny, fairy creature that she’d made. The women around them cooed and awed at her. She had the doe brown skin of her mother, and a full head of light brown hair.

Mike didn’t want to hold her, worried that something had gone wrong, that there was a cursed mark on his daughter. But Tatinelly knew that he would come around.

The second thing she realized was that somewhere in the house, there was a fire.

Marimar and Rey ran into the room to warn them, but the flames had raced up the stairs and now blocked their way out. Rey went to the window, but it was too dangerous to jump. Marimar threw herself on the ground, yanking at the carpet under their feet. She was knocking, keeping her head to the floorboards.

“What do we do?” Reina asked.

Tatinelly smoothed Rhiannon’s sticky hair. A smile tugged at her lips. She shouldn’t have felt that calm, but that’s how she was, the eye of a hurricane.

“Got it!” Marimar shouted as she pressed down and a latch opened on the floorboards. The way was dark, with old stairs leading down into who knew where.

“Mom said this is how she used to sneak out,” Marimar said, and waited for the others to file in. “Tati, you first.”

“I will slow everyone down,” she said. She handed Rhiannon over to her cousin. Marimar was terrified, but she gave her a reassuring nod and went.

“Go!” Tía S

ilvia shouted. Her hands were still covered in blood, so bright it looked like she was wearing gloves.

They went, one by one. Tatinelly wasn’t sure where she found her strength, but she got downstairs. Mike held her hand. He was terrified into silence, shaking, craning his neck to see the end of the passageway. Rhiannon didn’t cry out despite the roar of the flames or the scared hiccups Penny was letting out. The stairs were dark, illuminated by glowing dragonflies and lightning bugs. They zoomed back and forth, and Tatinelly knew that they were here to make sure Rhiannon was safe.

When they got to the bottom, they realized they were in the walk-in pantry, empty for the first time since the house came to be. The fire hadn’t reached the kitchen, and they hurried out through the yard and back around.

In the distance, Enrique was running away from the house, trudging uphill just as an ambulance and the sheriff’s Lincoln were speeding downhill. The volunteer fire department was two towns over and on their way, but they all knew it was too late. The stench of rot and decay around the house was replaced with smoke. Tatinelly stood downwind of it, covered in jackets and sweaters and anything her family could take off. If she closed her eyes she could imagine sitting around a fireplace, with the kind of family that was bonded by blood and roots and magic.

* * *

After hours of being unable to stop the flames, they simply watched it burn. Bathed in morning light, the house was nothing but a pile of ash and debris around a great tree with branches that reached for the heavens, surrounded by thousands of incandescent creatures.

Marimar was barefoot again and she still couldn’t tear herself away from the front of the house. It was the spark of Rey’s lighter that brought her back to the present.

Sheriff Palladino stepped out of his car and took in the scene. He had aged well, Marimar thought. The paramedics were on Tatinelly at once, taking her blood pressure and giving her and Rhiannon oxygen.

Marimar and Rey stayed close.

Incendiary Series, Book 1

Incendiary Series, Book 1 A Crash of Fate

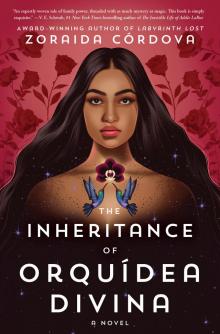

A Crash of Fate The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina

The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina Incendiary (Hollow Crown)

Incendiary (Hollow Crown) Labyrinth Lost

Labyrinth Lost Love on the Ledge

Love on the Ledge The Savage Blue

The Savage Blue Vast and Brutal Sea

Vast and Brutal Sea Life on the Level: On the Verge - Book Three

Life on the Level: On the Verge - Book Three The Vicious Deep

The Vicious Deep Luck on the Line

Luck on the Line Bruja Born

Bruja Born Illusionary

Illusionary Vicious Deep

Vicious Deep